How I Went To War - 8

Apart from our routine camp duties of manning the guns, guard and piquet duty, not to mention cookhouse fatigues (washing up and peeling mountains of spuds), we had a good measure of free time.

We would go swimming on the beach below the cliff a mile down a lane, or in the evenings wander down to the village for a drink or a bite of food in our favourite cafe owned by Mme. Andrews.

Rue Félix Fauré, Octeville-sur-Mer.

Our favourite café was at Mme. Andrews, "A la Denise" - on the right of the photo just beyond the cyclist.

One attraction here was her lovely daughter, Denise, who was perfectly charming but not for the taking as she was already affianced to a local Frenchman. To the credit of our unit and the supervision of Madame, there was never any misbehaviour on our part.

The locals were very friendly to us, especially the children who would spend hours at the perimeter fence watching our activities. Some of the chaps had a cheap laugh by teaching them rude English words but to make up for it would give the kids chocolate or sweets.

We learned that Mme. Andrews had married an English ‘Tommy’ during the 1914-18 war and that she kept an English atlas in her parlour behind the cafe. Sometimes, those of us whom she liked would be invited into the parlour for a drink of liqueur and to write our names and addresses in the back of the atlas. For her it was a nostalgic reminder of the ‘Tommy’ she had wed, but it could also have given her a lot of trouble if found by the Jerries during Occupation. (Upon the fall of France, she buried the atlas in her garden behind the cafe and it survived to be examined by me and the children when we revisited the village in 1961)

Jerry would send over twice-daily reconnaissance planes, always out of gun range (30,000 ft) and we could almost set our watches by his visits. One day a parachute was spotted falling some where to the east of Montivilliers, so it was likely that someone had got a shot at him.

Information on the progress of the war was usually based on rumour and I cannot recall ever having a briefing on the military situation.

The daily routine checking the levels of the guns with clinometers; the ‘lining up’ the guns so that the dials on the predictor read the same on the gun dials; the cleaning of the barrels and mountings; and simulated action for practicing drills, was part of everyday life essential for an efficient result.

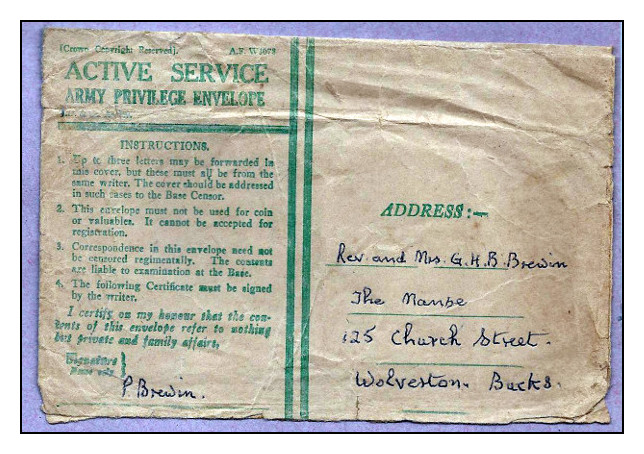

We received regular letters and sometimes parcels from home which were much appreciated. In the letters there was never any mention of enemy activity over England and we on our part were very careful not to reveal where we were at any one time. Indeed, our mail was censored by our own officers - Lt. Seymour and Lt. Pat Ellam - who were a couple of really good chaps, universally liked.

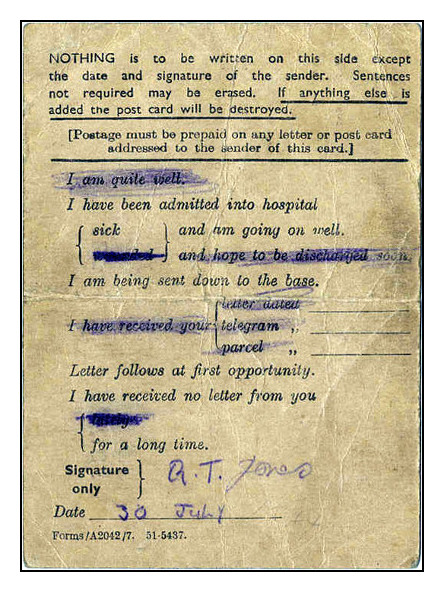

There were also the Active Service Privilege Envelope (the ‘green’ envelope) censored at Army HQ somewhere in the region and the Field Service Postcard which was printed with a few options such as: “I am well” etc. which one would tick as appropriate and sign it. This would accommodate those who for some reason did not wish to write a letter, or indeed could not do so.

Active Service Privilege Envelope

Field Service Postcard